By Olusegun Adeniyi

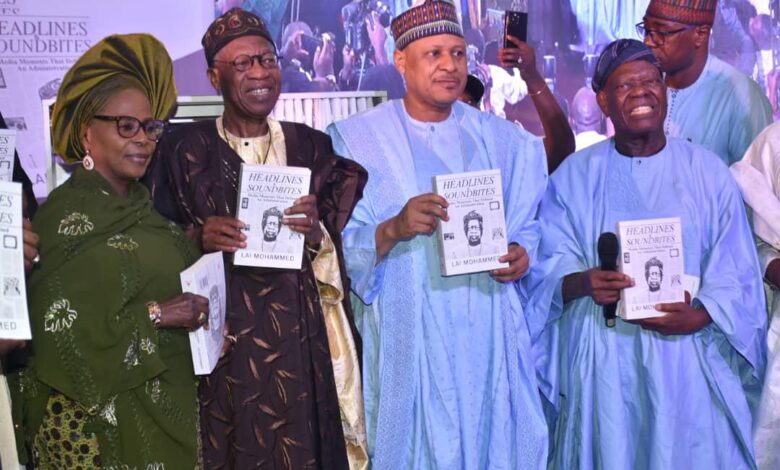

(Text of my review of ‘Headlines & Soundbites: Media Moments That Defined an Administration,’ written by the former Minister of Information and Culture, Alhaji Lai Mohammed, at the public presentation in Abuja on 17th December 2025)

With a first degree in French before going on to read Law, Alhaji Lai Mohammed is one of a few members of the Nigeria political elite with a second address. Before politics and government, he was an established lawyer, respected media practitioner and public relations guru. And after he left government, Alhaji Lai refused to hang around. He went back to private practice by joining ‘Ballard Parters’,a global government relations firm, as Managing Partner for Africa, focusing on public relations and public policy. On a personal note, I have known Alhaji Lai Mohammed since the beginning of the Fourth Republic when he served as the Chief of Staff to then Governor Bola Tinubu of Lagos State who is now the President of Nigeria. Alhaji Lai also happens to be one of the respected elders from my state, Kwara. Athough we had no close personal relationship, when he came to my office to ask if I would accept to be the reviewer of his book, I had no choice in the matter. I actually considered it an honour.

In the opening pages of ‘Headlines & Soundbites: Media Moments That Defined an Administration,’ Alhaji Lai made an important declaration: he is a “strong advocate of Africans telling their own stories from their own perspectives.” This commitment to indigenous narration is admirable and necessary. However, as I worked through this 584-page chronicle of his nearly eight-year tenure as Nigeria’s Minister of Information and Culture under the late Buhari who would have been 83 today had he been alive, I was reminded that telling one’s own story is not the same as telling the whole story, and that perspective, no matter how privileged, is not synonymous with objectivity.

This book, ‘Headlines & Soundbites: Media Moments That Defined an Administration,’ is many things at once: historical document, policy defense, and occasionally, an extended rebuttal to both the critics of the Buhari administration and Alhaji Lai Mohammed himself.The structure is ambitious, covering everything from town hall meetings and media tours to the controversial Twitter suspension and the #EndSARS protests. What emerges is a portrait of a minister who saw himself not merely as a government spokesperson, but as a strategic communicator tasked with “changing the narrative”—a phrase that appears repeatedly throughout the text and perhaps reveals more about the administration’s approach to information management than the author intended.

There is undeniable value in the insider account provided by the former minister. His chapters on the government’s communication strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic and the protracted P&ID legal battle offer useful insights into crisis management at the highest levels. The detailed documentation of media tours to territories hitherto controlled by the Boko Haram insurgents and the account of Nigeria’s digital switchover provide important context that was often missing from real-time reporting. Of course, the minister was meticulously careful in choosing what to highlight and what to hold back.

Alhaji Lai is at his best when he abandons the defensive posture and simply describes the mechanics of government communication. His explanation of the stakeholder engagement process, the rationale behind town hall meetings, and the cultural diplomacy embedded in hosting international conferences are genuinely informative. These sections will prove valuable to students of public administration and political communication. The stories are told with the methodical thoroughness of someone who understands that history will judge his stewardship in government long after the news cycle has moved on.

The chapter on Nigeria’s fight to repatriate stolen artefacts, including the Benin Bronzes, is particularly compelling. Here, Alhaji Lai’s passion transcends his portfolio, and one senses a minister genuinely engaged with issues of cultural identity and historical justice. Similarly, his account of the National Theatre’s restoration hints at what might have been achieved if the ministry had focused less on crisis management and more on its substantive cultural mandate. But it is in Alhaji Lai Mohammed’s treatment of the most controversial episodes of his tenure that the book both fascinates and frustrates.

The Twitter suspension, which he insists was misunderstood, receives extensive treatment. He provides the government’s rationale, documents the negotiations that preceded the platform’s restoration, and argues that the concerns by the Buhari administration about social media regulation were legitimate. Unfortunately, the chapter reads less like historical documentation and more like a legal brief, comprehensive, certainly, but selective in its engagement with opposing viewpoints.

The confrontation with CNN over its #EndSARS coverage is similarly presented as a victory for truth over “skewed and poorly sourced reporting.” As a journalist, I disagree with this summation. Alhaji Lai may well have legitimate grievances about the international media’s coverage of Nigerian events. However, the righteousness with which he dismisses CNN’s journalism sits uncomfortably alongside his own acknowledgment that government communication must be “tempered by transparency”—a phrase he uses in reference to the Bring Back Our Girls campaign.

This brings us to another troubling aspect of the book: Chapter Fourteen, titled “#ENDSARS: A Massacre without Bodies.” That title alone demands scrutiny. Alhaji Lai devotes an entire chapter to arguing against what he characterizes as the myth of a massacre at Lekki Tollgate on 20th October 2020. He may believe he is correcting the record, but the framing “a massacre without bodies” ignores the grief of families who lost loved ones during those protests, regardless of the specific number or precise circumstances.The judicial panel of inquiry set up by the Lagos State Government documented deaths and injuries. To reduce this complex tragedy to a semantic argument about the definition of “massacre” is to miss the forest for the trees. As the late Dele Giwa reminded us, “One life taken in cold blood is as gruesome as millions lost in a pogrom.”

Right from the introduction, Alhaji Lai Mohammed acknowledges that one motivation for writing the book was “to dispel a number of misconceptions.” This is a worthy goal. But throughout the book, there is a troubling conflation between “misconceptions” and “disagreements.” When Nigerians questioned the Twitter suspension, were they all simply misinformed? When activists criticized the government’s response to #EndSARS, were they all perpetuating falsehoods? When journalists challenged official narratives about security operations, were they invariably biased?

To be fair, Alhaji Lai Mohammed does not shy away from documenting the challenges he faced. He acknowledges operating in a difficult environment, dealing with an opposition determined to undermine the administration, and managing a president who was often reluctant to engage with the media. Given my own experience in another life, I can understand these challenges. But my concern is that there is little self-criticism or any willingness to concede that some of the administration’s communication failures were self-inflicted.

In his tribute to Buhari (Chapter One), Alhaji Lai describes the late president as a “friend, mentor and boss,” and throughout the book, this loyalty to the administration he served is on full display. This loyalty is admirable in its consistency. But it also limits the utility of the book as a historical document. Therefore, while future researchers will find valuable raw material here—press statements, timelines, policy documents—they will need to triangulate Alhaji Lai Mohammed’s account with other sources to arrive at a fuller picture.

Chapter nine titled, ‘Before the Ballot: Inside Buhari Administration’s Scorecard Strategy’, according to the author, was necessitated by the need to counter the narrative of the opposition before the 2023 general election with a media offensive that featured prominent officials. One of them is Abubakar Malami, SAN, who was then the Attorney General and Justice Minister. No fewer than 16 quotes of Malami, splashed over eight pages, are featured in the book where he highlighted the achievements of the Buhari administration, especially in the fight against corruption. One of the quotes from Malami reads: “The EFCC could only succeed in securing 103 convictions before the advent of the current administration. However, with the implementation of the National Anti-corruption Strategy, the EFCC has secured about 3,000 convictions.”

The last time I heard from Malami, he was writing an epistle from EFCC detention, throwing the same allegation that those ‘about 3000 people convicted people’ under the Buhari administration he served were also throwing at the time. A case of whatever goes around comes around.

Before I take my seat, let me commend Alhaji Lai Mohammed for this book. ‘Headlines & Soundbites’ is an important book, though not always in the ways its author intended. It is important because insider accounts matter, especially from someone who occupied a critical position for as long as Alhaji Lai did. It is important because it documents, in granular detail, the mechanics of government communication in 21st-century Nigeria. And it is important because it reveals, perhaps inadvertently, the deep disconnect between the Buhari administration’s self-image and its public perception.

Alhaji Lai Mohammed writes that he believes this account “will form part of Nigeria’s contemporary history, at least from my vantage point.” He is right. But vantage points, by definition, offer limited views. They show us what was visible from a particular position at a particular time, but they also hide what lay beyond the sight line.

Let me also express a personal disappointment. As the founding National Publicity Secretary of the All Progressives Congress (APC) whose candidate, the late Muhammadu Buhari, went on to defeat then incumbent President Goodluck Jonathan, Alhaji Lai Mohammed played a crucial role in the months leading to that election in 2015. But there is nothing about that episode in this book. There is also no reflection to contrast the role of a government critic which he was under Jonathan and information manager that he became under Buhari. It would have been helpful had the author given us a peep into whether the view of the road remains the same after moving from the passenger’s side to the driver’s seat. That, for me, is where the narrative should have started. But while this book is not what I was expecting, it is nonetheless still an interesting read.

At the end, the book’s greatest contribution may be unintentional: it provides an unvarnished look at how the Buhari administration saw itself and its critics. The worldview that emerges is one in which the government was perpetually misunderstood, consistently undermined by enemies both domestic and foreign, and forced to combat a relentless torrent of “fake news” and “misinformation.” There is some truth to this picture, since every government faces hostile coverage and unfair criticism. But the completeness with which Alhaji Lai Mohammed adopts this victim narrative suggests a troubling inability to distinguish between unfair attacks and legitimate criticism.

However, whatever may be our misgivings about the Buhari administration, ‘Headlines & Soundbites: Media Moments That Defined an Administration,’ offers glimpses into what happened in that era. But this is Alhaji Lai Mohammed’s story, told from his perspective. It deserves to be read and engaged with seriously. But it should not be mistaken for the definitive account of the Buhari administration’s relationship with truth, transparency, and the Nigerian people. That story is still being written, and it will require many more perspectives, including from the journalists Alhaji Lai Mohammed sparred with, the activists he dismissed, and the ordinary Nigerians who lived through those eight years with rather different experiences than the one documented in these pages.

To students of political communication, government media strategy, and contemporary Nigerian history, ‘Headlines & Soundbites’ is a book I will strongly recommend. Just remember to read it critically, with full awareness that in the contest between headlines and truth, soundbites and substance, the former too often prevailed during the years this book chronicled. Whether Alhaji Lai Mohammed recognizes this irony is unclear. What is clear is that he has given us a comprehensive record of how power sees itself and that alone makes the book worth the effort.